Kayly Ober is a new contributor to Towards Recognition. She has written this article below, which compares different proposed instruments advocating formal recognition of environmental migrants, exclusively for this blog.

You can read her bio here.

When you lose your home due to rising sea-levels, creeping desert sands, or harsh hurricane winds; you probably don’t have much time to stop and think: where will I go next? Fortunately, over the past few years, academics from all over the world have taken on the task of deciding not specifically “where next,” but “what next” for those displaced by climate change. Contributions to the legal debate have ranged from the defeatist to the pragmatic, but they have the advantage of always being interesting and adding to the discourse.

In October 2008, for instance, Jane McAdam and Ben Saul wrote a piece for the Sydney Centre for International Law called “An Insecure Climate for Human Security? Climate-Induced Displacement and International Law”. Most notably, the paper examines the concept of “human security” as a potential rally point for legal intervention. Human security is a relatively new term that defines security on a more micro scale, using the individual as a basis for the definition of security rather than the state; and according to the UN Development Programme more specifically guarantees “freedom from fear…and want, including safety from such chronic threats as hunger, disease, repression as well as…from sudden and hurtful disruption in the patterns of daily life” (p. 17). What human security affords climate migrants, McAdam and Saul write, is “flexible political solutions which can respond to immediate needs and provide much-needed domestic legitimation” (p. 2) and the possibility of the intervention of the UN Security Council, under the auspices of Chapter VII of the UN Charter in response to non-traditional threats.

Certainly, using the UN Security Council as a vehicle to legitimize climate migrants and as a response mechanism would be beneficial to both parties – climate migrants would gain a more binding legal status and institutions supporting the security agenda would gain traction in the developing world (p. 19). However, the authors also acknowledge that the use of human security as a legal reference may undermine current human rights law and “replace them with more ambiguous, non-binding, discretionary political agenda” (p. 22). In the end, the ability of existing international law, or new concepts such as human security, to extend full legal rights to climate migrants is dubious.

If a new legal framework to address climate migrants was created, then their status would be less tenuous, argue Frank Biermann and Ingrid Boas in their November-December 2008 Environment article “Protecting Climate Refugees: The Case for a Global Protocol”. They contend that a “separate, independent legal and political regime created under a Protocol on the Recognition, Protection, and Resettlement of Climate Refugees to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change” (p. 51) would work best. Using a protocol to an already established convention has its advantages: namely, the protocol could, in theory, build political support from almost all signatory countries to the convention and it could use this support as a basis to agree upon common principles like responsibilities and funding. The authors operate on the premise that migrants can be identified based on the vulnerability of their state to the effects of climate change; and said state would apply formally through the protocol to receive aid money to relocate their most affected populations; and where an executive committee will be in charge of determining recognition, grant protection, and facilitating relocation. While the idea of adding a protocol to a convention is a step forward, it lacks a coherent structure (as in the idea that “novel income-raising mechanisms, such as an international air-travel levy” would help generate funds for the initiative) and includes a limiting definition of climate migrant – only those displaced by “proven” climate change phenomena like sea-level rise or extreme weather events would be recognized. Additionally, leaving the responsibility up to states to lobby for funds to protect their own people would, by design, exclude the participation of most rogue states like Zimbabwe and Myanmar. And, as other analysts are quick to point out (like those below); the UNFCCC’s mandate extends more to state-to-state relations and focuses on prevention and mitigation efforts rather than remedial actions.

Bonnie Dochery and Tyler Giannini, alternatively, offer a more complex and fleshed out solution in the paper they published in the Harvard Environmental Law Review, “Confronting a Rising Tide: A Proposal for a Convention on Climate Change Refugees”. Since this is the most recently published paper, available in June 2009, they had the advantage of critiquing and tweaking Biermann and Boa’s suggestion. Dochery and Giannini, both lecturers at Harvard Law School, instead advocate for the use of a stand-alone convention that guarantees assistance, spreads the burden of responsibility and establishes an independent administrative system. To be more specific, their proposal can be outlined under three broad categories like this (p.373):

1) Guarantees of Assistance

a. Standards for climate change migrant status determination

b. Human rights protections

c. Humanitarian aid

2) Shared Responsibility

a. Host state responsibility

b. Home state responsibility

c. International Cooperation and Assistance

3) Administration of the Instrument

a. A global fund

b. A coordinating agency

The proposed definition for “climate change migrants” would specifically encompass six key elements:

c. Forced migration;

d. Temporary or permanent relocation;

e. Disruption consistent with climate change;

f. Sudden or gradual environmental disruption; and

g. A “more likely than not” standard for human contribution to the disruption. (p. 372)

While the definition does not include Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) as a legitimate group to be aided by the convention, the authors do state their intention to create a “narrow enough [definition] to be legally defensible but inclusive enough to cover those refugees most affected by climate change” (p. 374).

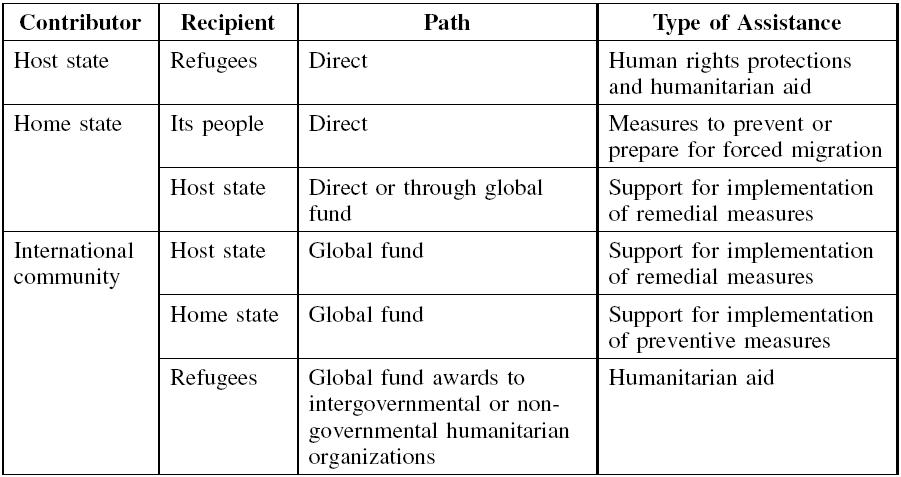

Under the agreement of shared responsibility, the authors feel that “host states should bear the primary burden of implementing guarantees” (p. 379), and “home states should facilitate the processes of orderly departure and family reunion” (p. 380) and crisis prevention, which would consist of mitigation and adaptation efforts that would stem the need for migration (p. 381). They also call for the international community, which have “contributed most to climate change,” to support the convention financially in a global fund – and where each state’s contribution should be based on a proportional scale of the amount it has contributed to climate change and its capacity to pay (p. 379). The following graphic breaks it down more succinctly:

This graph illustrates a measured and laid out plan to facilitate a funding mechanism within a climate refuge convention, something other plans, like that of Biermann and Boas, fail to completely render. Thus, a separate climate migrant convention seems the most carefully thought out, and ultimately, most plausible solution. The authors leave us with the task of propelling a convention based on past experiences, much like the Oslo Process, where the leadership of a group of like-minded states and civil society fomented a formal treaty. The next step, therefore, should be to encourage key states to bring the idea of a climate migrant convention to the table at UN sessions to negotiate draft text for Copenhagen. The negotiation of such a text looks set to be an arduous process, unaided by current positions within the UN. Here’s to hoping that negotiations work at a faster pace than climate change.

If you are a more visual person, the graphic below summarizes the key concepts discussed above.

| Perspectives | Proposed Instrument Toward Legal Recognition | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Australia | Human Security:

Focused on the individual as basis for security, as related to the right to safety from chronic illness, disease, repression as well as sudden disruptions in the patterns of daily life |

|

|

| European Union | Protocol:

A separate, independent legal and political regime needs to be created as a protocol under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) |

|

|

| United States | Convention:

A stand-alone convention that guarantees assistance, spreads the burden of responsibility and establishes an administrative system |

|

|

| United Nations | State Law:

States should build on existing international response mechanisms and ensure policy coherence between mitigation, adaptation, humanitarian responses |

|

|

Kayly Ober works at the Environmental Change and Security Program. The views expressed within this blog post are her own and not that of ECSP or the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. She is also a contributor at The New Security Beat.